From Supernatural Housework to White-Pots

Via Brooms, Witches, Brownies & A Remedy to Take Away a Hoarseness

Dearest Gentle Reader,

It may or possibly not interest you to know that this weekend it was time in my house for a big hoover. I really dislike housework but sadly, short of requesting supernatural help in the form of a brownie or similar individual, if I don’t do it, it remains undone. I also belong to a cat who seems to think that shedding fur is a full time job; so it was time for a special session. You know the kind, when you get out all the accessories and ends, most of which you don’t know the use for, and even consider moving furniture.

So obviously my brain tuned out from the actual activity and started considering the folklore of cleaning and stories about said supernatural assistants. There are definitely better places if you want actual leaning tips but these superstitions are pretty interesting.

I imagine lots of you associate brooms with witches and they rose to prominence as the way to travel for the witch around the Lancashire witch trials. There are lots of theories around why brooms and witches are connected as well as many stories associated with them including a wonderful Scottish traveller story told by Duncan Williamson but in this we are concentrating on how brooms are handled. If a broom was placed across a doorway, it was given to mean that either a witch lived inside the property or someone inside the property has been cursed. The person who picks up the broom is the witch so if you want to avoid a serious tripping hazard as well as not be judged as a witch it is probably best to leave brooms well away from doors.

In Yorkshire in particular, it was also believed that if you stepped over a broom on the floor and were unmarried, then you would give birth to a child out of wedlock. Definitely a good reason if nothing else to keep your brooms tidy in the days where that was not a usual and unhappy action.

You should also not sweep the house at night as you could sweep out your luck and there were even consequences for sweeping a broom over someone’s foot as it could mean they would not get married, or even go to jail. No-one mentions if these two are connected. There is also an American superstition that you should never bring a new broom to an old house as you will bring bad luck with you.

What I do know is that there is very little folklore that is hoovering specific, however the cat views it as a loud and scary demon that has entered his home which steals his toys and corks. He reacts as he does to all unwelcome intruders: growls, hisses and sprints for the stairs. This may have something to do with the instructions that came with this particular hoover which is actually a Dyson Animal and specifically state ‘do not use this cleaner to vacuum your pet’. Who needed to be told this? I have met friends of friends who insist their labrador loves a hoover but I remain unconvinced. They are very useful but distracting when you would frankly rather be doing anything else.

In this spirit and in honour of my briefly pristine floor surfaces I am going to bring you two stories of those supernatural beings that I mentioned who really do help those householders who treat them properly and bring misfortune to those who don’t. The first tale is a Staffordshire/Derbyshire tale as told by a WI member in Tissington in the 1930s and I read it Forgotten Folktales of the English Counties. It's a little sentimental but I can’t help but love it anyway. The second tale is from Scotland and shows that kindness can be found everywhere, even in the most unlikely of creatures.

Brownie stories always have food in them in one way or another, usually cream, bread or cheese related as these were considered a suitable thank you gift for brownies as they couldn’t easily make them themselves. They don’t usually like to be thanked directly and our first story is unusual in that, but it doesn’t directly reference the creature as a brownie either so that may be an explanation. There are many variations of brownie or house spirit and we have two very different looking creatures just in these two stories.

If you would like to hear more about fairies, food and obligation, you can watch a video of the talk I did on just that subject entitled ‘Food & Obligation: the Consequences of Giving & Receiving Food in Folklore, Folktales, Fiction’ but for now, let’s move to our first tale.

Food and Fire and Company

An old woman lived in a cottage on a hillside. It was a very little cottage with a door and one window and a garden in which the old woman could grow a few herbs.

The cottage had a good, stout door and a window and roof of stone slabs that kept out the rain, and a well-swept floor. She was a very clean and tidy old woman and in the comer she had dry brushwood and some piles of turves which the farmer brought her when he remembered. He was a kind man, but forgetful.

Besides the turves he sometimes brought her straw or hay to make her a soft bed in the other comer, and the farmer's wife sent her an old stew-pot to hang on the crook in the chimney and a mended patchwork quilt for her bed.

So there she was with a warm, soft bed, and a fire, and four stout walls and a good roof overhead. She had a wooden bowl and two wooden spoons that the farmer's boy had carved for her and oatmeal to sup when the farmer remembered.

Then one day the tinman came by with his loaded cart at a gallop. He was running away from the gamekeepers, for he had a load of ducks and rabbits under his tins.

The old woman went to her gate as the keepers came up. And there in the road was a nice tin mug that had rolled off the cart.

'He won't come back this way any more,' said the gamekeeper. You'd best have it to put in your neat little house. Very clean and comfortable it is.'

The old woman smiled at him and then she sighed a little. 'I be very lucky, I am,' she said. 'I've four stout walls and a good roof and a good door, a warm bed and firing and I'm making me a twig broom to sweep the hearth-but I wouldn't mind a bit of company.'

The gamekeepers went away again, but first one brought in another armful of dry branches for her and the other took a flat cake from his wallet and put it on the window-seat. 'Food and firing and company,' he said, 'and here you've got all three.'

After they had gone, the old woman broke the sticks neatly and put them in their comer and made up the fire and filled the stew-pot with spring water and shook up the bed nicely and swept the floor with a bunch of fern, and everything was clean and tidy again. So she put her last handful of meal in the pot to make a warm gruel for the morning in case the farmer forgot to bring her sackful. "Tis dusty stuff, meal,' said the old woman. 'I must make my twig broom tomorrow.'

Then she drank some spring water from the tin mug and broke a bit off the flat cake and went to bed. The next day the farmer came-his wife had remembered-and he brought meal, and a goose wing to sweep the hearth and a small gooseberry bush for the garden and battered wooden bucket for the water but it was half full of new milk.

'There!' said Farmer. 'Now you've got four stout walls and a door, a good roof and a good fire, food and drink, and a soft bed. What more can you want?' But he didn't remember to ask for any rent and he never did.

'What a busy time I'm having,' said the old woman when he had gone. Two visitors yesterday and another today-but I'd dearly like them to stay a bit for company. I'll make a dish of milk-porridge, that's what I'll do, and while it cooks I'll tidy up.'

So she made enough porridge for two and hung it to cook over the bright fire and she swept the hearth with the goose wing and carried out her bed to air in the sun while she took a sharp stick and dug a hole for the gooseberry bush and planted it. Then she carried back her hay bed in the quilt and shook it up in its corner and spread the quilt over it, and swept all the bits of hay off the floor with the goose wing into the fire and then she was quite ready to sit in the window-seat and drink warm milk in a tin mug and nibble a bit more flat cake and count all her blessings.

'How lucky I am,' she said. 'I have a beautiful spring at my gate, and a gooseberry bush in my garden, a good door, four stout walls and a good roof, a good bed, and a good fire, a crock ofmilk-porridge and half of the gamekeeper's flat cake, a bowl and a tin mug and two spoons-but Farmer forgot the turves and there are only four left-I must be careful. The sun is warm so I'll go to bed warm too.'

Then she said, 'But I'd dearly like someone to come and share it.'

So before she went to bed she poured out half of the milk-porridge into the howl and set a bit of the cake beside it and put it outside the door and called out into the listening dark, 'Come and eat a bit. You're very welcome whoever you are, but I'm afraid there isn't much.'

When she opened the door in the morning the bowl was empty and the bit of cake was gone. 'Now, who took that I wonder?' she said. 'They're very welcome but I'd dearly like their company a bit.'

Now four miles away on the other side of the valley was the Manor House. It was hundreds of years old and folk said it was lucky. It had a great garden full of roses and the scent of the red ones came on the wind across to the old woman and was so lovely she could have stood sniffing it all day, but today there was no scent at all. "Tis the rain maybe,' she said, though she felt it wasn't. 'I'll be soaked standing here.'

And when Farmer came he was soaked too, and so were the turves his wife had reminded him to bring, and of course he couldn't keep the carthorse standing in the drenching rain so he was off and away fast, but he did pass on a bit of news first.

'The old Squire died in London and a rich London nephew has come to the Manor with a parcel of fine city servants. The old servants won't work for him since he turned out the luck.'

'Oh dear, whatever did he do?'

'He found the bowl of milk and a bit of bread put by for "you know who" as has been done for hundreds of years and he threw it to his dog. Things won't prosper for him and he won't get any fine servants to bide there.'

The old woman felt quite upset, what with the wet turves, and the farmer's boots had made such a mess, and she was bent two-double with the aches in her bones, it took her nearly all day.

'I'll bake a couple of flat cakes,' she said, "twill take off my aches and pains.' So she kneaded them and laid them to cook on the warm hearth. Then she remembered to put out the tin mug and the last of the keeper's cake and call out her welcome. 'I shall have porridge and cake of my own,' she thought, but the rain fell and the turves wouldn't catch and the fire just smouldered and the old woman sat and shivered. Then, out of the night came a strange voice and something scratched on her door.

‘Oh dear oh,

Where can I go,

In rain and snow?

Oh dear oh,

What can I do?

Let me come in

And stay with you.’

'Poor thing,' said the old woman, 'I'll ask it in out of the rain.' Then she thought a bit-'It may be a ghost! Well, the poor thing needs comfort instead of wandering about-or it may be Summat Else,' but she called out bravely, 'Come in and welcome, whoever you are, though the fire don't burn very well!' And a thin, brown hand slid round the door and Summat Else slid round it too. The old woman hobbled to close the door and out of the comer of her eye saw something small and brownish slither along the wall and leap up into the chimney. The rain poured in and the wind blew until she had barred the door.

There was just a spark in the embers so she blew them into a faint glow and crawled into bed. 'You chose a good spot if it's still warm,' she called out, 'but the fire won't light us and warm us tonight. I'm sorry there's no porridge for you.' Then she shivered and went to sleep.

She woke suddenly and lay watching a warm light that glowed in the cottage and flickered on the rafters and the stag's hom pegs that held the roof slabs in place. Where did the light come from and what was that lovely smell of baking? She sat up puzzled; the fire was flaming, the porridge was cooking, the two cakes were brown and smelling lovely, and there was a neat pile of brown, dry turves stacked near the fire.

The old woman looked and looked and then she called out, 'Thank you kindly whoever you are and now we'll have a bit of supper.' Then she got up and poured out the milk-porridge into two portions and she put one cake into one of the bowls to stand on the hearth and she ate the rest herself. Oh, she was hungry! Then she called out again, 'Thank you kindly,' and went back to bed and fell fast asleep.

In the morning the sun was shining and there came a knock at the door and there was Farmer. 'You sleep late,' he said. 'My missus wants to know if you've such a thing as a rosebud in your hedge. She wants it for the well-dressing down in the village. 'Tis a pity you live so far out, with that flat rock over your spring you could make a fine picture in flower petals for the judges to see.'

The old woman sighed. 'Ah, but I can't stoop to pick 'em and I can't climb to get 'em, though I'd like fine to make a picture with flowers over my stream. Here's the rose for your missus.' When he went away she sighed again. "Twould have been something to think about and I do love flowers and the well-dressing is very pretty to see.

“Dear, dear, how late it's getting-I must get tidied up and bake some more cakes when I've got the fire going.” But when she went in the fire was burning. There were two cakes on the hearth, her bed was made and the floor swept. She was so surprised that she sat down and ate her breakfast without another word.

'I shall have time to do a bit in the garden,' she said, when she had finished. 'I wonder if I could find a flower or two for my rock.' Then she opened the door again and the cottage was filled with a lovely scent.

'How beautiful those Manor roses scent this morning air. You could almost think they were at my gate.' And that was exactly where they were, great piles of crimson petals, heaped neatly beside her spring.

There were other flowers too, blues and yellows and whites and pinks. The old woman gave a gasp of joy. Then she spread wet clay on the rock and set to work. 'Nobody will come this way,' she said, 'but I'll just see if I can get finished before the church bells ring, even if the judges won't see it.'

So she worked and she worked and somebody must have helped her for she had just finished putting the last petal into place when the church bells rang out and she heard voices-it was Farmer's cart with the judges in it and he had brought them round this way to the village so that the old woman might have a peep at them (he was a very kind man). They did more than take a peep. When they saw the rock and the spring and smelled the scent of the red rose petals they all said together it was beautiful. Then they went away.

In the evening they came back and some of the villagers too, and they gave the old woman the prize, three silver pennies. 'You and your red rose petals,' said the villagers, 'if you could run about I'd say you'd walked eight miles to pick those roses. There isn't a single red rose in all Manor gardens today, not one, and the new squire is so angry that he went back to London after he'd given the judges lunch. He was so sure he was going to win the three silver pennies with all his great gardens against our little bits. I'm glad you got it, living all alone as you do.'

The old woman just smiled at them and the farmer drove off with them. Then she went indoors again-she looked at the firelight, the steaming porridge, the cakes baking on the hearth, the pile of turves and her neatly made bed. The floor had been swept. She put her three silver pennies on the window seat and sat down to her supper.

'How lucky I am,' she said at last. 'Here I sit with Food and Fire and Company. Thank you kindly, whoever you are.'

The Brownie of Ferne-Den

There have been many brownies known in Scotland, and stories have been written about the brownie of Bodsbeck and the brownie of Blednock, but there is a better story about the brownie of Ferne-Den.

Ferne-Den was a farmhouse that stood on the edge of a glen, and had got its name from it. Anyone who wished to reach the dwelling had to pass through the glen. People believed a brownie lived in the glen, and that he never appeared to anyone in the daytime. But at night he was sometimes seen, stealing about like an ungainly shadow from tree to tree, trying not to be seen, and never harming anybody by any chance.

Like all brownies that are properly treated and let alone, he was always on the look-out to do a good turn to those who needed his help. The farmer often said that he did not know what he would do without him. For if there was work to be finished in a hurry at the farm - corn to thrash or winnow or tie up into bags, turnips to cut, clothes to wash, a kirn to be kirned, a garden to be weeded - all that the farmer and his wife had to do, was to leave the door of the barn or the turnip shed or the milk house open when they went to bed, and put down a bowl of new milk on the doorstep for the brownie's supper. And when they woke the next morning the bowl would be empty, and the job finished better than if they had done by themselves.

This might have proved to them how gentle and kindly the creature really was. But nearly everyone about the place was afraid of him, and would rather go a couple of miles round about in the dark when they were coming home from church or market, than pass through the glen and run the risk of catching a glimpse of him.

The farmer's wife was so good and gentle that she was not afraid of anything. When the brownie's supper had to be left outside, she always filled his bowl with the richest milk and added a good spoonful of cream to it, for, she said, "He works so hard for us, and asks no wages, so he well deserves the very best meal that we can give him."

One night this gentle woman was taken very ill, and everyone was afraid that she was going to die. Her husband was greatly distressed, and so were her servants, for she had been such a good mistress to them that they loved her as if she had been their mother. But they were all young, and none of them knew very much about illness, and everyone agreed that it would be better to send off for an old woman who lived about seven miles away on the other side of the river, who was known to be a very skilful nurse.

But who was to go? For it was black midnight, and the way to the old woman's house lay straight through the glen. And whoever travelled that road ran the risk of meeting the dreaded brownie. The farmer would have gone only too willingly, but he did not dare to leave his wife alone. And the servants stood in groups about the kitchen, each one telling the other that he ought to go, yet no one offering to go themselves.

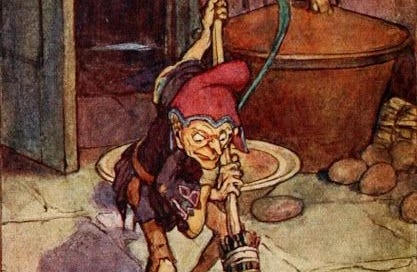

Little did they think that the cause of all their terror was within a yard or two of them behind the kitchen doo. It was a queer, wee, misshapen little man, all covered with hair, with a long beard, red-rimmed eyes, broad, flat feet, just like the feet of a toad, and enormous long arms that touched the ground even when he stood upright.

He listened to their talk with an anxious face. For he had come up as usual from his hiding-place in the glen, to see if there were any work for him to do and to look for his bowl of milk. And he had seen from the open door and lit-up windows, that there was something wrong inside the farmhouse, for at that hour it usually was dark and still. So he had crept into the entry to try and find out what the matter was.

When he gathered from the servants' talk that the mistress was ill, his heart sank within him. For he loved her so dearly and she had always been so kind to him, And when he heard that the silly servants were so taken up with their own fears that they did not dare to set out to fetch a nurse for her, his contempt and anger knew no bounds.

"Fools!" he muttered to himself, stamping his queer, misshapen feet on the floor. "They speak as if I was ready to take a bite off them as soon as I met them. If they only knew the bother it gives me to keep out of their road, they would not be so silly. But if they go on like this, the bonnie lady will die among their fingers. So it strikes me that I must go myself."

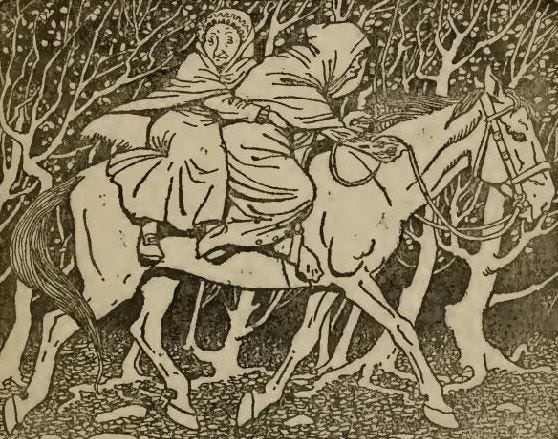

So saying, he reached up his hand and took down a dark cloak which belonged to the farmer, and was hanging on a peg on the wall. He threw it over his head and shoulders to hide his ungainly form somewhat, and hurried away to the stable. There he saddled and bridled the fastest horse that stood there.

When the last buckle was fastened, he led it to the door , and scrambled on its back. "Now, if ever you travelled fleetly, travel fleetly now," he said; and it was as if the creature understood him, for it gave a little whinny and pricked up its ears; then it darted out into the darkness like an arrow from the bow.

In less time than the distance had ever been ridden before, the brownie drew rein at the old woman's cottage. She was in bed, fast asleep, but he rapped sharply on the window. And when she rose and put her white-capped old face close to the pane to ask who was there, he bent forward and told her his errand.

"You must come with me, goodwife, and quickly, if the life of the lady of Ferne-Den is to be saved," he commanded, in his deep, harsh voice, "for there is no one to nurse her at the farm up there, save a lot of ignorant servant wenches."

"But how am I to get there? Have they sent a cart for me?" asked the old woman anxiously. For as far as she could see, there was nothing at the door save a horse and its rider.

"No, they have sent no cart," replied the brownie, shortly. "So you must just climb up behind me on the saddle, and hang on tight to my waist, and I'll take care to land you at Ferne-Den safe and sound."

His voice was so masterful that the old woman did not dare to refuse to do as she was bid. Besides, she had often ridden when she was a lassie, so she made haste to dress herself, and when she was ready she locked her door, and was soon seated behind the dark-cloaked stranger with her arms clasped tightly round him.

Not a word was spoken till they approached the dreaded glen. Then the old woman felt her courage giving way. "Do you think that there will be any chance of meeting the brownie?" she asked timidly. "I would rather not run the risk, for folk say that he is a dangerous creature."

Her companion gave a curious laugh. "Keep up your heart, and don't hem and haw," he said, "for I promise you that you'll see nothing uglier this night than the man that you ride behind."

"Oh, then, I'm fine and safe," replied the old woman with a sigh of relief; "for although I haven't seen your face, I am sure that you are a true man, for the care you have taken of a poor old woman."

She relapsed into silence again until the glen was passed and the good horse had turned into the farmyard. Then the horseman slid to the ground, and turning round, lifted her carefully down in his long, strong arms. As he did so the cloak slipped off him, revealing his short, broad body and his misshapen limbs.

"In all the world, what kind of man are you?" she asked, peering into his face in the grey morning light, which was just dawning. ''What makes your eyes so big? And what have you done to your feet? They look more like toad webs than anything else."

The queer little man laughed again. "I've wandered many a mile in my time without a horse to help me, and I've heard it said that over-much walking makes the feet unshapely," he answered. "But don't waste time in talking, goody. Go your way into the house. And listen: if anyone asks you who brought you here so quickly, tell them that there was a lack of men, so you had to be content to ride behind the brownie of Ferne-Den."

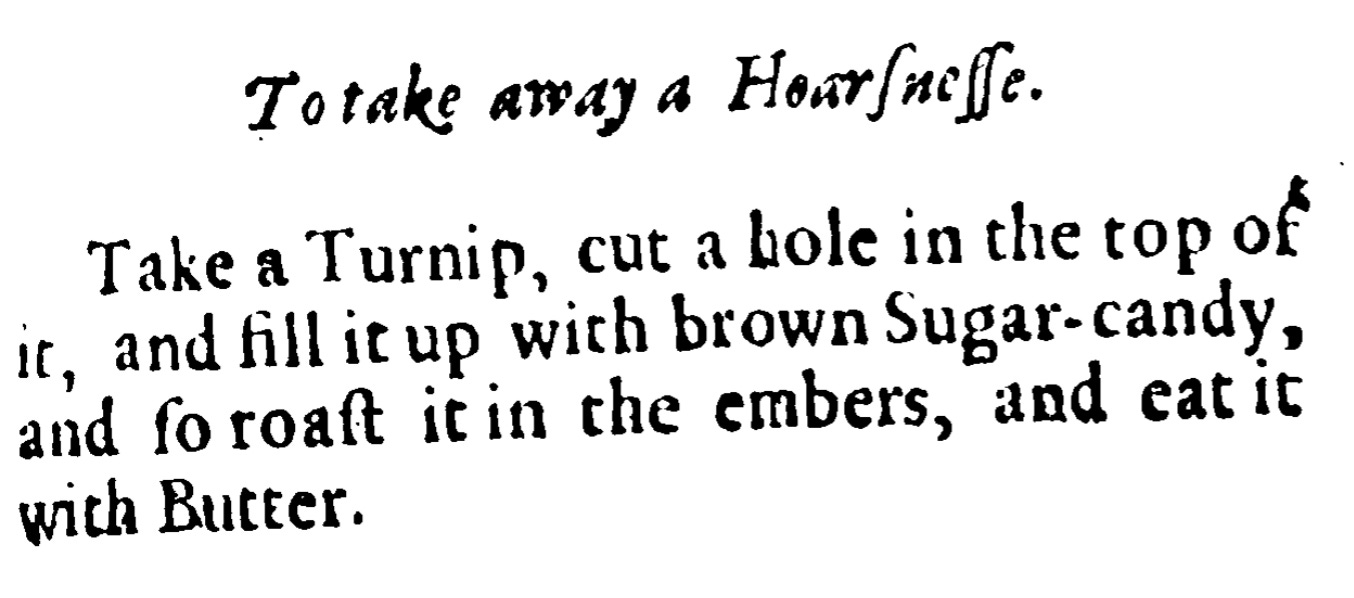

I just have time to share our remedy and recipe with you. How do you feel about this remedy. I do love turnips but a strepsil is easier to keep in your small bag of useful things in your rucksack. I will perhaps keep this handy for when a hoarseness comes up at home. I think it might work on the having nice things to eat to make you better principle of healing. This remedy is from ‘A Choice Manual of Rare & Select Secrets in Physick and Chyrurgery as practiced by the Right Honourable, Countesses of Kent, late deceased’ from 1653.

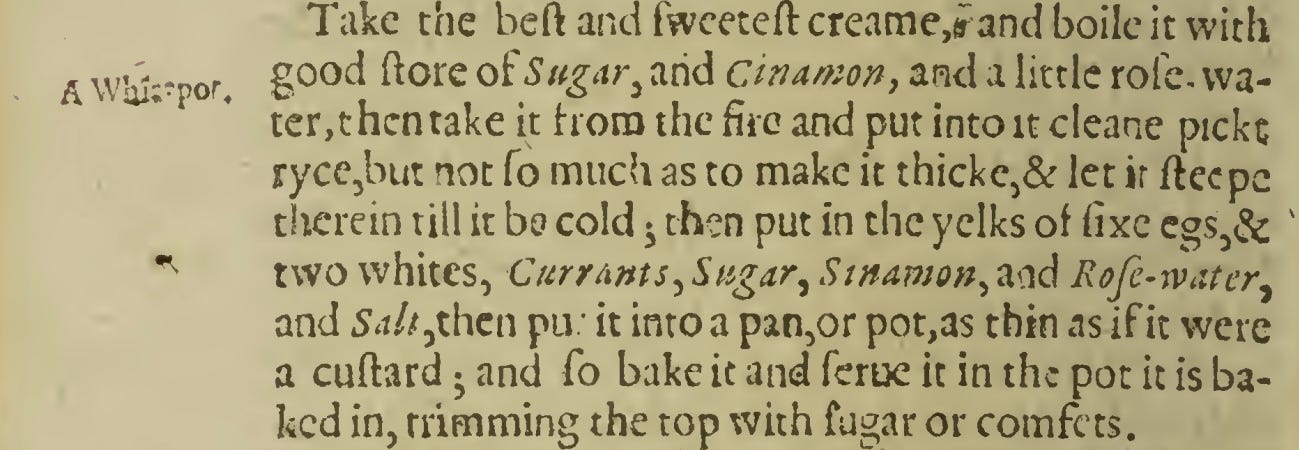

How about our recipe? This is essentially an incredibly luxurious, rich, spiced rice pudding from Gervase Markham’s 1631 edition of The English Housewife. White pot usually refers to a slightly later dish which was from Devonshire and had thinly sliced bread instead of rice. I’m not sure if they are connected by anything but being a delicious baked custardy type of pudding as I haven’t had time to research it. They are definitely both related to the white medieval dishes known as blancmanger but I would happily be a taste tester to check for differences between the two. Just for history, you understand, not for spiced, baked, custardy goodness.

Now, Gentle Reader, I must bring this letter to a close. Please don’t hesitate to get in touch via the comments or via any of my social media profiles/my website . If you have enjoyed this and would like to read further such nonsense and have not yet subscribed, please don’t hesitate to subscribe for free at the button below. You’d be very welcome and it would be a joy to write to you.

Loved the brownie stories! They are certainly my favorite of the good folk 😊

Thank you…life is magical with the right mind set.